Blog

Waves, Sands, Winds: Patina of the Era in the Fluid Image of Nature

1 October 2021 Fri

Thoughts on capturing the transforming image of nature...

I contemplate the phrases we often eviscerate by weaving them redundantly into our words, those we find too colloquial and seek an alternative for, or those we have long grown inured to. Idioms, sayings, expressions… Hearing a phrase constantly causes it to lose its true meaning after a while. As a photographer, and someone who likes to think over and write on photography, the phrase “capturing the moment” through photography is perhaps the most cliché of them all.

When I think of “capturing” or “withholding” a moment, what I visualize is either a frame shot during a hasty incident, an iconic image that begets history, or images from my personal family albums. These are all powerful images on personal, social and political levels. But what if we relay this phrase of “capturing the moment” to a sphere where changes are not discerned from one moment to another; what would greet us in that sphere then? I ponder nature, which we associate with silence, stillness or lentitude. The image of nature, which underwent a transition and change in its own rhythm, or, the movement of which infinitely assured us until recently. This image, each moment of which is imagined to be motionless; how does its capturing in a certain place at a certain time in the universe, to a single frame correspond the photography’s particularity “of capturing the moment”? While it comes forth as a trademark of documentary photography or photojournalism, in the conventional nature/landscape photography it begins to take on a new meaning, a tendency to “preserve memory”.

The subgenre labeled as “landscape photography” in English, covers both the scenery, nature and landscape photography in its Turkish translation. What’s more, Jackie Higgins broadens its frontiers and adds herein the likes of Andreas Gursky, Olafur Eliasson and Sohei Nishino in her book, Why It Does Not Have To Be In Focus. 1 That being the case, subjects like the city, modernization and globalization fall under this subgenre. According to the author, landscape photography does not only have to do with nature but also with gaze and memory. If we take it a step further, we are encountered by a social and political anxiety – in the wake of new movements that address climate crisis and ecology. Artists who are concerned about the environment and climate change, who explore the humanity’s destruction of nature or who attach importance to the recycling treatments participate in this campaign for awareness by means of landscape photography. As such, in this text, I will try to analyze the photographs of Michael Kenna, whose works are derived from a more traditional and primal sense of the subgenre; Boomoon, who treats the subjects of nature as a more corporeal substance, and Olaf Otto Becker, who developed his praxis in respect to the global warming and natural destruction caused by humankind.

Michael Kenna, Frosty Morning, Onuma Lake, Hokkaido, Japan, 2004.

54 x 44 cm. Silver print.

Michael Kenna is an artist who deals with this subgenre of landscape photography in a classical and aesthetical manner. In his considerably minimal and silent photographs, he engenders an open-ended construct through his technical decisions that he meticulously takes. There is an open door in his photographs, which allows the viewer to situate herself/himself within the frame and to diffuse her/his emotional state onto the image. As a matter of fact, the artist who is utterly influenced by the Japanese haiku, constructs elaborate images that are submitted to the interpretation of the viewers. Frequently employing long exposure, Kenna creates an impression of timelessness whereas his use of light alludes to a dimensionless quality. Therefore his photographs oscillate between reality and dreams, between the artist himself and the viewer.

It is conceivable to separate Kenna’s photographs into two groups, namely the silent cityscapes and images of nature. "The essence of the image often involves the basic juxtaposition of our human-made structures with the more fluid and organic elements of the landscape. I enjoy places that have mystery and atmosphere, perhaps a patina of age, a suggestion rather than a description, a question or two. I look for memories, traces, and evidence of the human interaction with the landscape. Sometimes I photograph pure nature, sometimes urban structures, more often both together." Explaining his work with these words, the artist takes the fluidity of nature and the patina of the age he mentions and melts them in the same pot by means of his technical details and visual resolutions. 2

The state of silence and simplicity in Michael Kenna’s works steer me in the direction of another photographer I would like to mention; Boomoon. Shaped around the phenomenon of water, Boomoon’s oeuvre reciprocates the phrase “capturing the moment” with a rather odd duality. If taken as an image, water is a compound that seems to preserve its nature and qualities from thousands of years ago; however, when it’s seen from the perspective of geography and movement, or more importantly climate and ecology, it takes on a form that constantly changes in a way that is impossible to repeat twice. In his series Bosphorus, produced in 2017 on the Strait of Istanbul, he looks at the water, in fact literally into the water. The series opening with the images of water, which we take for granted, becomes enriched in the subsequent photographs with its living beings; towards the end of the series, the water itself sort of comes to life. Referring to this liveliness, and taking the water as a corpus, Boomoon imparts that “the encounter with fish and jellyfish may have been inevitable as they form the body of the Bosphorus.” 3

Boomoon, Untitled #10201, Fjallsjokull, 2010.

185 x 281 cm. Laserchrome print.

Four years after Boomoon’s exploration of the Bosphorus and water as a corpus, an exceedingly negative incident happened in the Sea of Marmara, where the Strait flows and the sea was engulfed with mucilage as the aftermath of environmental pollution and climate change. Covering the sea’s surface with enormous piles, the mucilage continues to consume the oxygen in the waters, even during its disintegration. Although this predicament in the Marmara Sea, which was taken for granted as a wastewater for years, is no longer in our short-range or visible on the sea surface, the sea is still fighting for its life. This is a pathway, a politics of destruction that leads to the sea’s fight for life; it’s a destruction we are all accountable for.

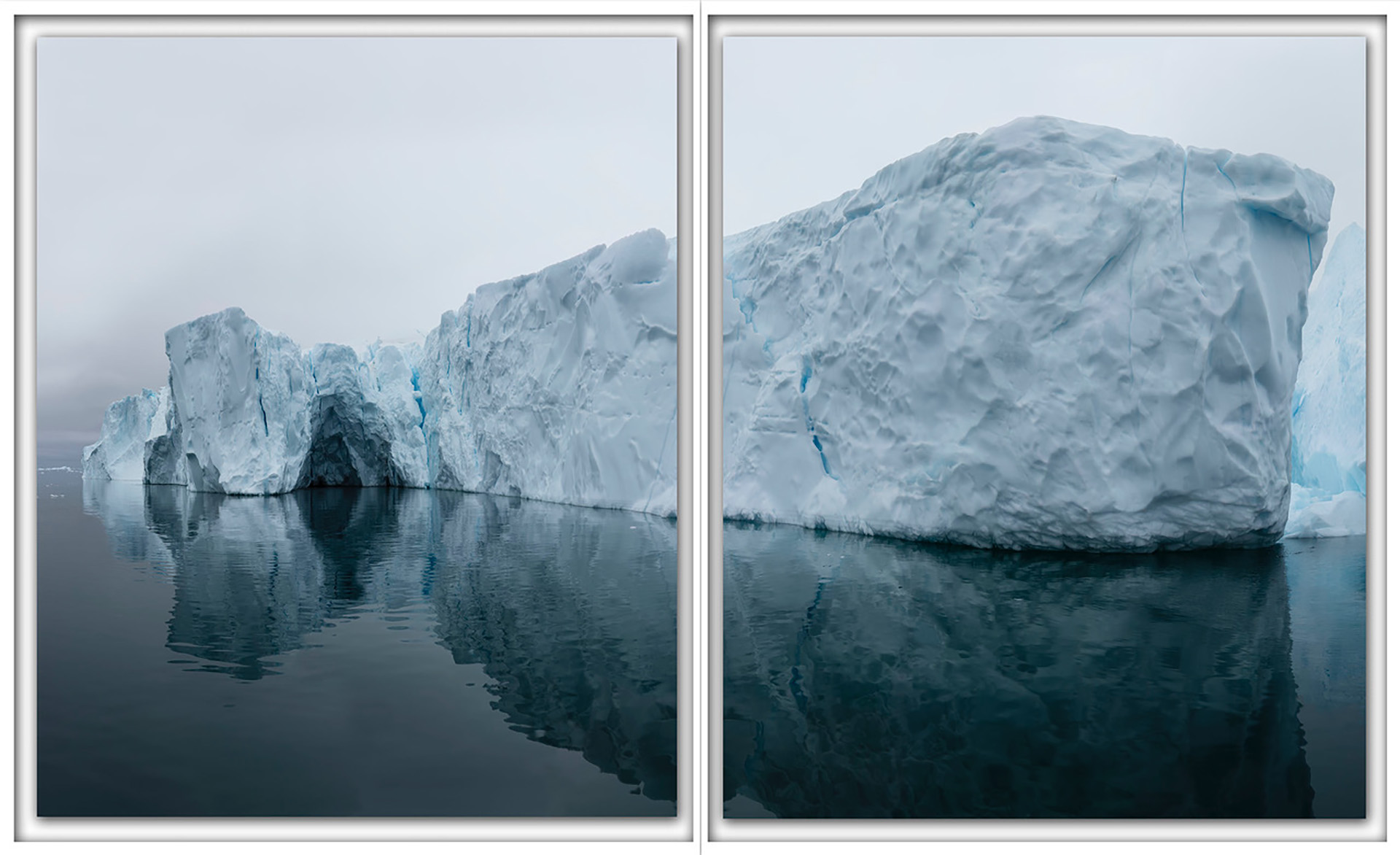

Humankind’s destruction on nature has reached an undeniable level, even when human figures are not apparent in the image. A photographer who successfully conveys this to his works is Olaf Otto Becker, whose work I personally follow with admiration. The artist, who studied communication and political sciences, then worked with painting for years, seems to have been highly influenced by his education and past experiences. Having conceived numerous works in the subgenre of landscape photography over the course of 30 years, the artist has visited Greenland in 2001, and detected a change in the icecaps he photographed only several years ago, which compelled him to focus on the subject of climate change and humankind’s impact on nature. Regarding his practice and approach to his subjects, Becker says that “we will appreciate and protect only the things we have got to know.” 4 This statement applies for the young forests that face extinction. The artists who explores the subjects of nature, destruction and modernity at once in his long-term projects, yields breath-takingly beautiful images which suffuses the viewers with grief and shame.

Olaf Otto Becker, , Ilulissat 15, 07/2015, 69° 12' 18“ N, 51° 10' 17“ W, 2015.

223 x 364 cm, Pigmentprint on Aludibond, diptychk.

When the works of these three photographers are seen merely from a visual perspective, a diagonal movement of waves, sands and winds sweep you away. It is as if the images are dancing with one another. When their subjects and the hallmarks of the last decade are considered however, a different perception of depth comes forward, almost like an addition of a new axis to the coordinates. This axis encompasses the artists’ exploration of humankind’s delicate relationship with nature on distinct simplicities, political levels and metaphors. Which is probably why, I enjoy viewing them together; I sense that they are playing tricks on my mind.

It is evident that in the coming years, we will be addressing the questions as to what art can do to counter the changing phases of our era, or that we will be seeing more of its reflections in art. A pursuit for solution, which involves the diversity and the plurivocality of artists from different geographies and origins, is the ultimate wish. The selection from the Borusan Contemporary Art Collection, curated by Leyla Ünsal and presented as part of the 212 Photography Istanbul festival is a fraction of this pursuit for solution. Suggesting a narrative regarding the humanity’s relationship with nature, history and life, Another Apocalypse is Possible exhibition is taking place at Akaretler Sıraevler no.37-39 between October 1-11, 2021.

1- Higgins, J. (2013). Why It Does Not Have To Be In Focus. London: Thames&Hudson.

2- For detailed information, see: An interview with Michael Kenna, Borusan Contemporary Blog, March 2020.

3- An interview with Boomoon on his Bosphorus Project, Borusan Contemporary Blog, June 2020.

4- An interview with Olaf Otto Becker, Borusan Contemporary Blog, May 2020.

ABOUT THE WRITER

İpek Çınar

Born in 1992 in Ankara, İpek Çınar has completed her studies in Political Sciences at METU in 2018 and began her graduate studies in the ‘Art in Context’ MA programme at UdK Berlin in 2020.

Working predominantly with the photographic medium since 2011, Çınar tells stories that seek to convey an idiosyncratic language by blending photography with writing. In addition to her photographic production, she contributes to various publications with essays, interviews and series of articles; prepares exhibition catalogues and acts as a content advisor, particularly on photography.

Çınar was among the coordinators of The Booklab project by Frederic Lezmi and Okay Karadayılar; she worked as an instructor for the Darkroom and editing workshops at Ka Fotoğraf Geliştirme Atölyesi (Photography Enhancement Atelier) in Ankara and acted as a content advisor for the photography documentary of TRT 2, İzler Suretler (Faces Traces).

She opened solo exhibitions at Poligon “The Shooting Gallery” and at Ka Fotoğraf Geliştirme Atölyesi and took part in numerous group shows in Turkey and abroad. She has been invited to international artist residencies, workshops and festivals where she participated in exhibition and lecture programs. İpek Çınar, who is also a member of AICA Turkey, is the co-editor of Orta Format Magazine since 2015 and she loves the magazine very much.