Blog

Some notes on an expansive view of Sol LeWitt in three parts

23 December 2024 Mon

PART ONE:

“This is not to be looked at”: The evolution of Sol LeWitt’s artistic philosophy and its potential influences

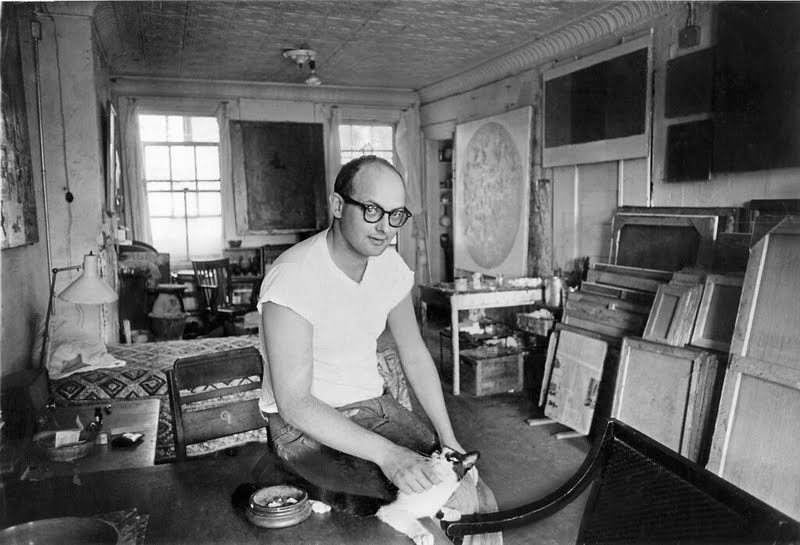

In a rare photograph of Sol LeWitt in his studio, we see the artist in a plain white shirt, framed in the foreground looking up at the lens stroking his cat. Across from the table, on the other side of the room, we see a number of canvases piled up against the wall, faced backwards. This black and white image featured in The New York Times, taken in 1961, predates LeWitt’s first solo exhibition by only a few years. The article discussing the tough working conditions for artists, presents LeWitt here as a painter among other struggling artists who are forced to take on second work. 1 At the time, as is well documented, LeWitt was working as an hourly paid reception clerk at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA, or as he and his peers called, “The Modern”). During his five years at the MoMA, LeWitt formed a network of friendships and ideas with fellow artists Robert Mangold, Robert Ryman, Dan Flavin, Gene Beery, and writer-art critic Lucy Lippard. In these years, LeWitt began moving away from painting to what would become formative in defining what came to be known as Conceptual Art. 2

In the context of the mid-Twentieth century, the world on the brink of a nuclear holocaust, endless wars as well as anti-colonial uprisings against imperial powers, came an overt disbelief in truth or language of politics and governance, as expressed by Herbert Marcuse in the One-Dimensional Man (1964): “What mattered was not “truth”, but getting the intended result. One does not “believe” the statements of an operational concept but it justifies itself in action – in getting the job done.” 3 After the Second World War, some western artists turned to silence and emptiness as in the works of Samuel Beckett for example, or near silence and muteness as in the works of John Cage, as the only authentic form of production. Reacting against the emotionalism of existentialist approaches and romanticism of abstract expressionism, together with the growing influence of language-centred theories in the humanities, there was a clear shift in attention from author/subject to the system within which language and production circulated. This tendency, broadly described within the visual arts at the time as the “dematerialisation of art” 4 , was also an extension of the distrust towards subjective and expressive representations. 5 Thus, 1960s minimalist and conceptual works signal on the one hand, in the anti-aesthetic tradition of Duchamp, a detachment from the primacy of material presence, allocating precedence to the idea or the thought process, as well as a return to a mechanical form of production embodied as a desire to evoke clarity and comprehension through systems of thought. 6

Sol LeWitt in his studio, July 31, 1961. The New York Times.

Photo of Sol LeWitt by Neal Boenzi

Eventually, Sol LeWitt became one of the most significant American artists of the post-war era, and frontrunner of the emphasis on ideas over end results and system-based conceptual art. However, LeWitt remained relatively unknown until his participation in the Eleven Artists (1964) exhibition at the Kaymar Gallery curated by Flavin. Lucy Lippard recalled in an interview that “by 1966, Sol was really becoming well known and being very successful.” She continues. “When I first met Sol, he was older than the rest of us, but he hadn’t hit his stride. He was doing sort of funny Jasper Johns-related, targety-looking things with thick paint, different colors of the Jasper Johns targets that were—really red, yellow, and brown; red, yellow, and blue… He just hadn’t quite figured out where he was.” 7 The Kaymar Gallery show was mentioned as the first collection of “avantgarde deadpans” including paintings by Frank Stella, who was deemed “outstanding”. 8 LeWitt’s artworks were also mentioned in high esteem (“excellent”), albeit accompanied by a sly jab at the artist’s seemingly undecipherable works that “kills the observer with his own curiosity”. 9 Though pronounced as austere by journalists, LeWitt’s work and writing was celebrated by leading art writers and critics, paving the way for a burgeoning era of art criticism on the dematerialisation of art and objecthood. Stella’s work, which LeWitt was a keen admirer of, catalysed the minimalist movement and became definitive examples of minimalist painting. He maintained a ‘reductionist’ approach to art that sought to demonstrate that for him, every painting is "a flat surface with paint on it—nothing more", and disavowed conceptions of art as a means of expressing emotion. Around this time, LeWitt moved from Minimalist toward Conceptual Art, stressing the idea behind the work over execution. LeWitt’s employment of systems to instruct the execution and realisation of artworks have also been regarded as programmatic and often cited for its emphasis on rationality and a lack of emotion. Stella’s insistence that “what you see is what you see” and LeWitt’s precise definitions of conceptual art where the “idea becomes the machine that makes the art” 10 (echoing Warhol’s famous remark “I want to become a machine”), became two notorious formulations adopted as unofficial mottos of the minimalist and conceptual movements, respectively.

By 1965, LeWitt had his first solo exhibition in New York and quickly became a beacon among his peers. The artist was in his fifties when he received high-status recognition, participating in several group shows that became seminal in establishing minimalism at the time, namely the Primary Structures and the 10 exhibit at Dwan Gallery, both in 1966. Roberts highlights that “friendships [at the MoMA] provided the scaffolding for LeWitt’s success as an artist in the late 1960s.” 11 LeWitt’s artistic career took off, his methodical approach to art making increasingly gained attention, together with his writings on art. 'Sentences on Conceptual Art' (1967) and 'Paragraphs on Conceptual Art' (1969), becoming one of the most widely cited artists' writings of the 1960s, exploring the relationship between art, practice and art criticism. 12

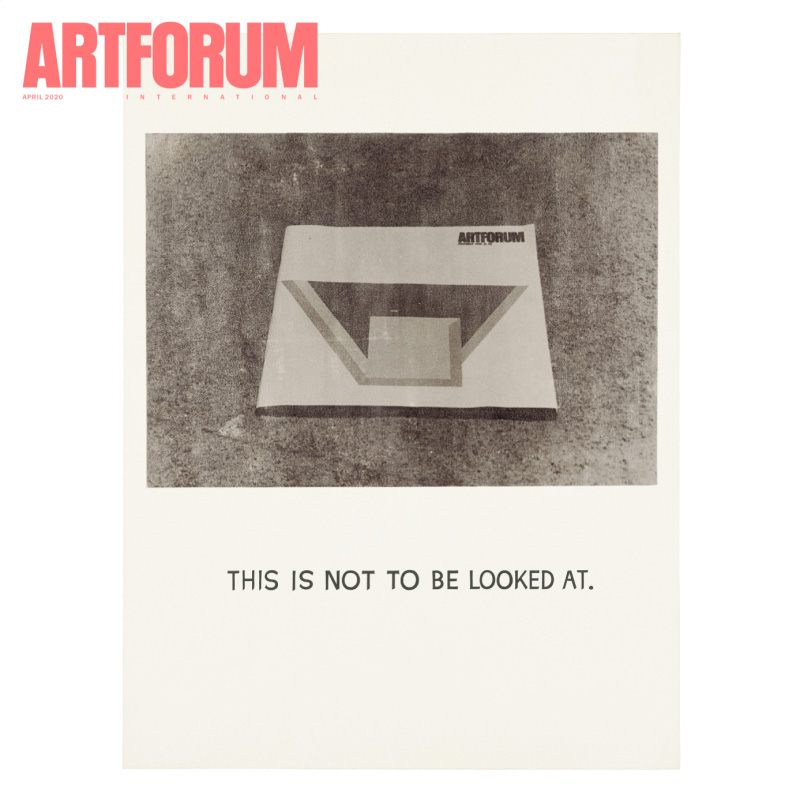

Artforum cover of April 2020, featuring John Baldessari's work 'This is not to be looked at' (1974), which in turn displays the Artforum cover of November 1966, with one of Frank Stella's Irregular Polygons works (Union III, 1966) as cover image.

Over the course of the decade, the paintings Lippard mentions faded into obscurity, especially after 1968 when Lippard invited LeWitt to participate in a group show at the Paula Cooper Gallery where he contributed his first wall drawing.” His artistic practice, including his three dimensional ‘structures’ as he referred to them, was built on the premise that the artist was a thinker, the producer of a concept that could generate a work of art. Many of his works, including his wall-drawings, exist as a set of instructions and diagrams that communicated the ‘idea’ of each work, introducing the notion of multiplicity and plurality in the production and realisation of a work, challenging the notion of the work of art being a singular object, extending beyond ‘objecthood’ as later discussed by Lippard.

It is also important to remember that Sol Lewitt was writing about art in the USA at a time when art criticism was very influential in shaping the understanding and making of art. American artists in the 1960s predominantly came to be known as artist-writers for actively participating in the interpretation and theoretical scholarship of their works. Art writers, critics and artists commingled in daily life and print media, especially in art magazines, which became an institutional field for critical discussions not secondary to the voice of scholarship predominantly overridden by physical institutions like museums and universities. In print media, artists took an authorial voice in the interpretation and definition of their artworks, talking back to the critics, so to speak. One of the cutting-edge magazines of the time, which maintained its leading role in contemporary art writing internationally, is Artforum. Established in 1962 in San Francisco and later moved to New York, the magazine with its characteristically unique square format, held its heyday in the late-1960s and to the late 1970s, becoming a flagship arena for quality discussions on new art forms, namely minimal art, conceptual art, body art, land art and performance art, with regular contributions from theorists Michal Fried, Rosalind Krauss, Lucy Lippard alongside artists Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd, Nan Goldin and Robert Morris, among others.

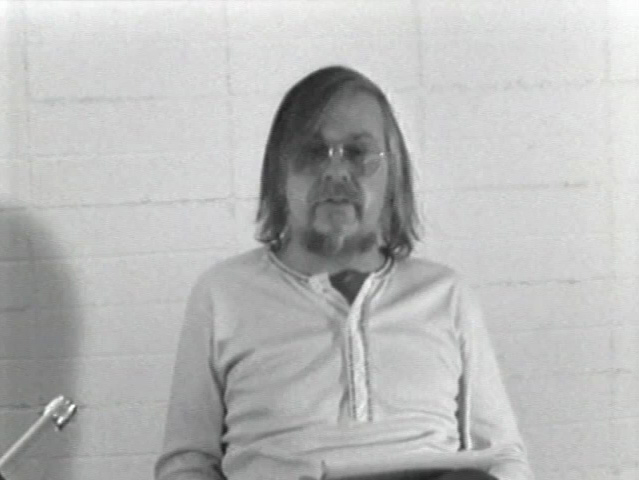

John Baldessari, John Baldessari sings Sol LeWitt, 1972.

Artforum not only featured in-depth articles, reviews, and inspired heated debates but also showcased leading contemporaneous artworks on its cover as frontispiece. John Baldessari’s reproduction of the cover in his work titled This Is Not To Be Looked At (1966-68) is a playful criticism of the characteristics of featured works, the nature of art, how it comes into being and their interpretation. The appropriation of the cover featuring Frank Stella’s painting Union III from the Irregular Polygon series (1966), while highlighting the growing popularity of the artist, pays tribute to the essence of conceptual art, by “pointing” to an idea, and reproducing something from a new angle. The image is a black-and-white photographic print of a reproduction of the magazine’s cover that reproduces a painting on canvas. In 2020, the artwork made the cover of Artforum extending the “layering of preexisting images demonstrated by Baldessari’s scepticism about artistic originality.” 13 The caption “This Is Not To Be Looked At.” while echoing Rene Magritte’s linguistic game, paradoxically implies that visual contemplation is neither the best nor only way to engage with art. 14 Baldessari’s suggestion that art can be something other than an optical experience is also exemplified by his 13-minute video tribute to LeWitt’s writings on art. In “Singing Sol Lewitt” Baldessari reads, or rather recites Sentences on Conceptual Art. 15

LeWitt’s structures and wall drawings dominated his reception for most of his career, becoming the two pillars that best demonstrated the vital elements of his artistic ideology and practice. This seems to be the case for many artists of this period. Perfunctorily, minimal and conceptual artists like Frank Stella, Donald Judd or Sol Lewitt are defined by works from their early-mid careers, primarily because they were formative to the establishment of the movement itself. When we think about Judd, for example, we immediately think of his stacks. Likewise, Stella’s work is customarily associated with stripes, especially in his Black Paintings, and LeWitt with his monochromatic structures and later wall drawings. More often than not, these artists are characterised by the pinnacle or milestones of their careers, however they continued to work late into their lives, all turning to more colourful and vibrant variations of their early works. Judd’s later installations imitate the repetition of his early glossy stick series; for example, Untitled,1991 installation, engages the space in a state of looking. Likewise, Stella’s hard edge acrylic paintings morphed and expanded into different syncopations and forms, expanding into three-dimensional space.

Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #917,

from his solo show Sol LeWitt Wall Drawings in 1999, courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.

For his 1999 exhibition at the Paula Cooper Gallery, presenting Wall Drawing #917 for the first time; LeWitt commented “I wanted to do something that was the opposite, instead of subtle and restrained.” 16 Sol Lewitt’s later works, which will be discussed in detail in the next part of this series, are alluringly colourful, in stark contrast to his paired back monochromatic structures and systems-based drawings from the 1960s. The printworks in the Borusan Contemporary collection can be seen as prime examples of LeWitt’s move from his subtle works to the most brilliant colourful artworks which he continued to make until the final decade of his career.

1- The article features the photograph of the artist with the byline “Sol LeWitt’s work earned him 1,000 last year, the first money he had ever taken in from sales of his paintings.” Nan Robertson, “Artists Forced To Take Side Jobs”, The New York Times. July 31, 1961. P. 21, 41.

2- Veronica Roberts traces the ways that friendship among artists working at the MoMA shape their artistic development, particularly how Lewitt’s conversations with Flavin helped catalyse LeWitt’s shift from painting to modular structures to serial systems. See Veronica Roberts, “Front Lines: LeWitt at Work at the Modern (1960–65)” in Locating Sol LeWitt, ed. David S. Areford. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021).

3- Tony Godfrey, Conceptual Art (London, New York: Phaidon Press, 2001) p. 148

4- Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 (New York: Praeger)

5- Simon Morley, Writing on the Wall: Word and image in modern art. (Thames and Hudson, 2007). P. 102

6- Hal Foster in The Return of the Real ties this to a “return to the earlier conceptualism of Duchamp and Dada,” as quoted in Tony Godfrey, Conceptual Art (2002) p. 386. See Chapter 1. In Hal Foster, Return of the Real (MIT Press, 1997) pp. 1-35. However, LeWitt has often refused this direct association in interviews. See “Sol LeWitt in Conversation” in Sol LeWitt Structures 1965-2006, ed. Nicholas Baume. (New York: Public Art Fund and New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011). Pp. 110.

7- Oral history interview with Lucy Lippard, March 15, 2011. Conducted by Susan Heinemann. Elizabeth Murray Oral History of Women in the Visual Arts Project. Available at: https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-lucy-lippard-15936

8- “Art: Avant‐Garde Deadpans on Move; Kaymar Gallery Shows Recent Works”. The New York Times. April 11, 1964. P. 22. Available at: https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1961/07/31/issue.html

9- “Art: Avant‐Garde Deadpans on Move; Kaymar Gallery Shows Recent Works”. The New York Times. April 11, 1964. P. 22.

10- Sol LeWitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” in Art in Theory 1900-2000 An Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Massachusetts, Oxford, Victoria: Blackwell Publishing, 2002). p. 846. The article was originally published in Artforum, Summer, 1967.

11- “LeWitt in all directions”. June 9, 2021. Available at: https://yalebooks.yale.edu/2021/06/09/sol-lewitt-in-all-directions-part-2/

12- Lovatt, Anna (2012). "The mechanics of writing: Sol LeWitt, Stéphane Mallarmé and Roland Barthes". Word & Image: A journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry. 28 (4): 374–383. doi:10.1080/02666286.2012.740187. ISSN 0266-6286.

13- John Baldessari, This Is Not to Be Looked At, 1966-1968. Object Caption. Museum of Contemporary Art Website. Available at: https://www.moca.org/collection/work/this-is-not-to-be-looked-at

14- John Baldessari, This Is Not to Be Looked At, 1966-1968. Object Caption. Museum of Contemporary Art Website. Available at: https://www.moca.org/collection/work/this-is-not-to-be-looked-at

15- Baldessari’s work represents an important bridge between early conceptual art principles and its interpretation and expansion into postmodern, interdisciplinary practices such as performance and digital / multimedia media art. See John Baldessari, Singing Sol LeWitt. Available at; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-LleBVS5_ho&ab_channel=SanFranciscoMuseumofModernArt

16- David S. Areford, Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints (Yale University Press, 2020). p. 11