Blog

Present Distant

27 July 2021 Tue

An essay on the opsigns and sonsigns in Ali Kazma’s videos.

“I’ve always thought I had time.” 1

Last Year in Marienband, 1961

During those years I just started working in a gallery, one of the things I enjoyed the most in office hours was to pass time with the videos of Ali Kazma. Rewatching the Taxidermist which has been shown on numerous occasions as part of the Obstruction series, I had thought that I have grasped the palpable relationship between the viewer’s temporality and the video, which is a medium of Ali’s production aesthetics. While the taxidermist was restoring a dead animal as an object (or perhaps as a sculpture), the only thing we could not witness was the documentation of the very process from start to finish. Ali Kazma was not interested in the chronological flow of time just like he was not interested in telling a story; he was rather urging the viewer to pay attention to something else, namely the time itself, which goes by as these images are being watched. While the taxidermist was filling up the flayed skin of the unfortunate fox, striving to recharge it with its former vitality, the sequences selected and sorted by Kazma were shaping the viewer’s time that was allocated to follow the video.

In an interview publicizing his most comprehensive exhibition in France, which opened in 2017 at the Jeu de Paume, the artist has elucidated what making films meant for him by quoting a statement of Tarkovsky: sculpting in time. 2 Kazma has skillfully managed to apply this approach in his earliest works and developed it further in the subsequent periods of his career. Subterranean, which gave its title to the exhibition at the Jeu de Paume, as well as Absence and Electric shown in the same show are part of the copious video archive of the Borusan Contemporary Art Collection. As such, this essay aims to define the distinct positions of these three works within the context of Ali Kazma’s production aesthetics in a scholarly sphere in which I presume the conceptual transmissions between videography and cinematography are possible.

In the preface for the second volume of the English translation of his books wherein cinema is analyzed as a philosophical phenomenon, Gilles Deleuze denotes that Tarkovsky defines cinema as the “pressure of time” in the shot 3 According to Deleuze, Tarkovsky questions the division between the shot and the montage with this definition. Although the shot is taken in a “present”, the image cannot exclusively exist in the “present”; it takes part in a web of temporal relations and “present” merely slips by in this web. The thing that makes it possible for Ali Kazma to sculpt in time is the build-up of sequences he solidifies with the “pressure of time” that are captured in the shooting plan. Likewise, the subjects the artist chooses to film also draw him away from the nowness, which is among the pillars of the documentary cinema. In Kazma’s works, the working of a craftsman or the running of a machine is shaped with the activities that are constantly recurring, done in the past, recorded during the shot and that will continue in the future; the image is not trapped in a “present”. This tendency in his production aesthetics explains why he has reservations about the label of documentary, and his distance to “present” enables us to re-read his videos in respect to Deleuze’s philosophy of cinema.

Two fundamental concepts employed by Deleuze to analyze the history of cinema are movement and time. Cinema 1, which spans over the period between the advent of cinema and World War II, focuses on movement, whereas Cinema 2 reaching forth to our day, emphasizes time. These two books, which are not adequately covered even by the Cinema Studies despite its eminent institutionalization as a field of study, are substantial resources to contemplate about the moving and still image. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta, who have translated Cinema 2 from its original in French to English under the supervision of Gilles Deleuze, note that the book does not propose a novel cinema theory and that it is not written to analyze cinema with existing philosophical concepts, but that the main purpose of these two volumes is to work with concepts that are derived from cinema on a philosophical level. 4 Granting the fact that Ali Kazma is not a movie-maker, I reckon that the “opsign” (optical sign) and “sonsign” (sonic sign) concepts that Deleuze thoroughly addresses in Cinema 2 do offer new possibilities to interpret his production aesthetics. Before moving onto the analysis of the videos, I should briefly discuss why Deleuze splits the cinematographic image in two, namely the movement-image and the time-image.

According to Deleuze, the breaking point that changed the paradigm in the making of cinematographic image is the World War II and he explains the rationale behind his thesis as follows: “The fact is that, in Europe, the post-war period has greatly increased the situations which we no longer know how to react to, in spaces which we no longer know how to describe. There were ‘any spaces whatever’, deserted but inhabited, disused warehouses, waste ground, cities in the course of demolition or reconstruction.” 5 In the films of directors who turned their camera to such spaces, time appears for itself and creates paradoxical movements. 6 For Deleuze, the division between the movement-image and the time-image is so constitutive that the emergence of time-image is reminiscent of the birth of Impressionism in the history of painting. Just as Impressionism has transferred the painting to an optical space, the time-image founds to construct cinema over the optical and sound situations. 7

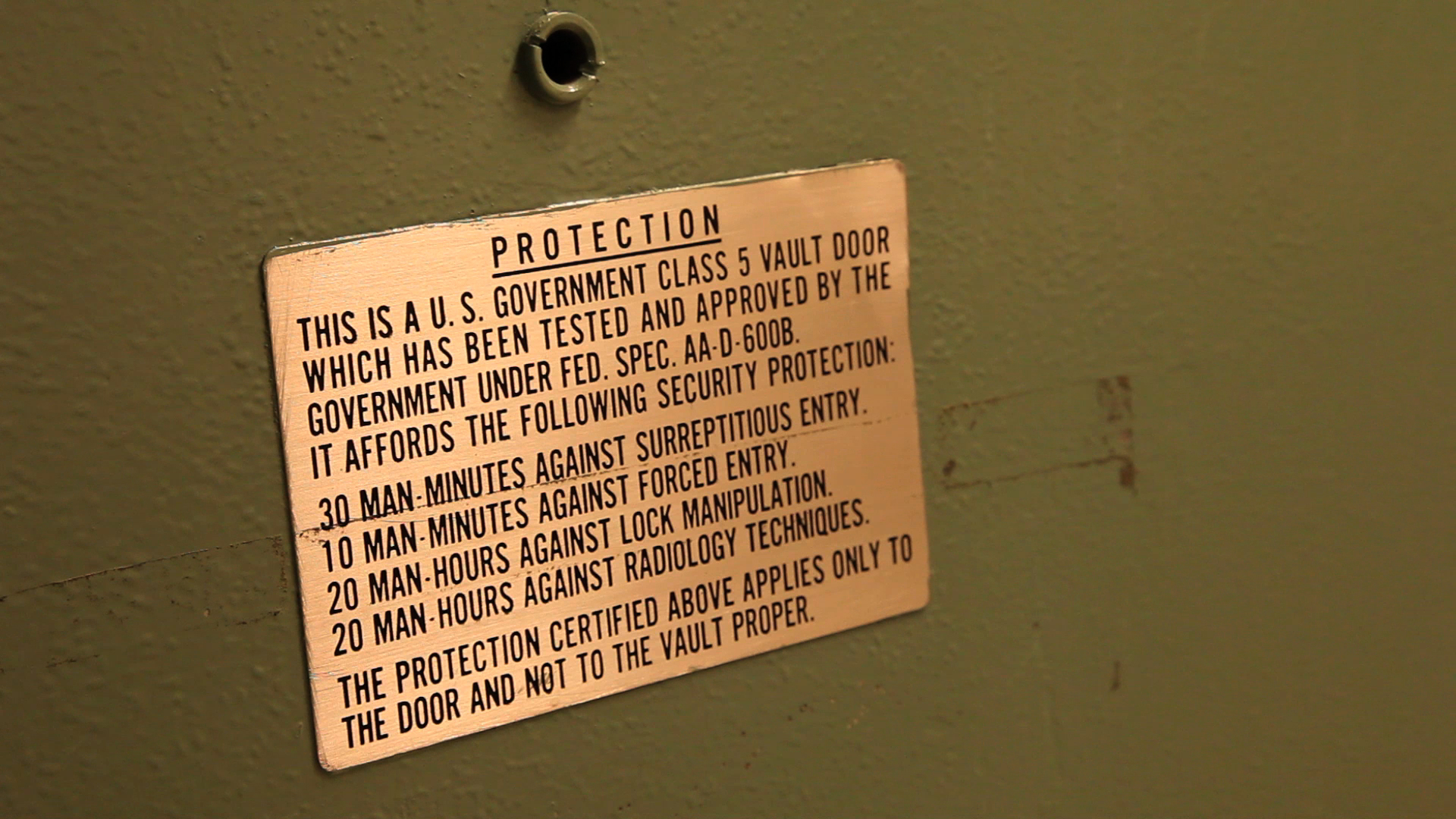

In his video work titled Absence, Ali Kazma records a space that gives the very inkling of “any spaces whatever” that is described by Deleuze, a space that has lost its function with the attenuation of yet another war, that is the Cold War. Throughout the video, we watch how a NATO base in Netherlands that was deserted at the outset of 1990s surrenders to the nature. For the first time in Kazma’s videos Absence does not show any activity of production and it comprises of image and sound pieces that the artist has collected from the space. To rephrase this with a terminology that Deleuze would opt for: in this work the artist is merely interested in optical and sound situations, as in his other works. According to Deleuze, “optical and sound situations can have two poles – objective and subjective, real, and imaginary, physical and mental. But they give rise to opsigns and sonsigns, which bring the poles into continual contact, and which, in one direction or the other, guarantee passages and conversions, tending towards a point of indiscernibility (and not of confusion)”. 8

The opsigns Kazma selected for Absence spins around different poles as well. By directing his camera towards a military base that has never been the site of a hot conflict, the artist points out to a space where the perceptions of actual and imaginary threat intertwine. As opposed to the physical reality of now-idle warehouses, shelters, cabins and recreational areas, the warnings and instructions written on various signboards recall the state of vigilance that was expected of the base personnel. The figure of Mickey Mouse waving his hand from the tip of a plane give us clues of unexpected preferences, like the obsolete payphones hinting the private lives of the former residents outside the base. The sound of the wind hovering through the bushes pervading the emptied lot and pounding the camera’s microphone, the tweeting of the birds rising from the woods surrounding the facilities, the buzzing of the broken fluorescent light, the howling sound in the ammunition stores that are rundown from lack of proper care, the noise of the still-running equipment and much more often the absence of sound are some of the sonsigns that the artist embeds in the video. Unlike his earlier works, Absence proceeds with inertia instead of movement, which is perhaps why the opsigns and sonsigns are in their most visible and audible forms in this work.

When discussing the relationship between cinema and linguistics, Deleuze objects Christian Metz’s theory that the cinematographic image is inherently narrative. He argues that the narration is an outcome of the web of relations in which the image exists. 9 As the image is liberated from the movement, it moves away from the narrative; opsigns and sonsigns questioning the pertinence of movement-image emerge. 10 We may assume that Ali Kazma’s rejection of a narrative regime of image ever since the beginning of his career has taken him to the sphere of the time-image. Moreover, Deleuze’s argument that the optical and sound situations help us to grasp the unbearable 11 has a counterpart in many works of Ali Kazma. The pain penetrating through the skin in Tattoo, the well-versed butchering process in Slaughterhouse, the dexterity of chopping meat in Butcher, which most viewers would not find so appealing, the skull-piercing operation in Brain Surgeon, the banalized violence that reigns in Laboratory and the dazzling tension in Kinbaku are some of these unbearable things that the artist chooses to show in his videos. Having said that, these videos by no means turn violence into narration or pornography; Kazma does not invite the viewers into any emotional state. Each of these hard-to-watch actions, in their mundane course and ordinary reality, are presented as the links in a chain of optical and sound situations, and not as per their excesses or shortages.

Cinema 2 inquires the instances of opsigns and sonsigns predominantly in the Italian Neorealism. However, considering Ali Kazma’s videography just along the lines of approaches that this movement offered may not be sufficient to understand his production aesthetics. Kazma’s style is closer to the aesthetic ideals of Alain Robbe-Grillet who is discussed by Deleuze on the same plane as Italian Neorealists. Although the autonomous material reality 12 of the objects and settings that Visconti incorporates into his cinema is traceable in Kazma’s videos, the artist’s insistent endeavor to free the image from emotions parallels with Robbe-Grillet the most. Robbe-Grillet’s ideal of defining the visual material by use of lines, surfaces, and sizes 13 seems to be substantiated in Kazma’s corpus of work. Alongside this, the human figures that the artist rarely decides to show conjures up the extras in the films of Robbe-Grillet with their repetitive actions, distinct gestures, expressions devoid of sentiments and solemn postures that evoke a feeling as if they bear an existential secret. The chief element that distinguishes Kazma from Robbe-Grillet is their distinct attitude towards tactility. Robbe-Grillet’s radical apprehension of image rejects tactility too while the act of touching is critical, even pivotal for Ali Kazma. In an interview, the artist was telling that he was fascinated about how the world and people come into a physical contact through hands, how they transform one another, and that this interest is the reason why he includes hands so often in his works. 14 Among the works where hands are visible in their most hypnotic manner are Clock Master, Clerk and Jean Factory. In the videography of the artist, the hands are the organs of re-constituting the belief in this world 15 , which Deleuze deems as the main object of the modern cinema.

Beginning from his Obstruction series onwards, Ali Kazma surveys the humankind’s connection to this world in the production processes, which encompass the activities necessitating handcrafts to those entail industry. In his video work, Subterranean, he turns his camera over to a facility of heavy industry. The video opens with trajectories crossed by the beams of light that reflect off metal surfaces with distinct absorption rates. We subsequently watch the inside of a tunnel wherein a person can easily move forward if s/he is squatting. The sophisticated mechanical plant at the end of the tunnel as well as the perfection of the rings that create it, demonstrate that we are confronted with a structure that is the product of an engineering of the highest level. What we see is a pipeline that is manufactured to be used for the natural gas transmission and the immense scale of the production is revealed in the wide-angle frames. Assembled in accordance with the volume of interiors the artist shows us, the industrial acoustics get amplified in the wide-angle shots and muffled in narrow spaces; the echoing sonsigns ensure the continuity between diverse images.

In Subterranean, the young man in the pipeline moves back and forth, upholding himself with his hands, looking left and right, not because he is perplexed but because he oversees details we cannot spot. Throughout the video, we observe other members of the team who are responsible for the perfection of this structure we watch from within and without. Once again, the sculpture-like posture of the masked welder who faces the camera and the recurring gestures of the figures who move along in the pipeline as if they are planning an impossible escape recall to minds the extras of Robbe-Grillet. Even though Ali Kazma never lets the figures he chooses to show to become parts of a narrative, or to turn into characters, etched into the memories of the viewers nonetheless, these figures appear almost on the verge of ontological distinctions. A striking example of this is evident in the video work Cryonics, where an officer with a morose expression performs his guard duty between life and death, controlling the units that contain human bodies and brains which are frozen in this center with the hope that they would be re-vitalized in an unforeseeable future. The optical situations referring beyond the visible and known, seems to be caught on the artist’s radar with the Resistance series that also include Cryonics.

Ali Kazma, Subterranean, 2016.

Two channel, synchronized HD video.

The artist’s mastery in putting the welding process on film carries our gaze to extra-terrestrial dimensions at times, despite our knowledge that Subterranean shows a plant of heavy industry. It seems as if the neon cobalt colored smoke fuming on an oblique surface rises from another planet; as if the thick fog in bright yellow-auburn color palette brimming over a pipe, whose surface appears to turn into molten metal with the flame of the welding, has broken loose from the explosions on the surface of a star and has plunged down in the video. The artist’s interest in the heavy industrial plants begins with Rolling Mills where he focuses on an iron and steel factory and continues in other works. The optical situations pointing out to the energy created by heat is eminently visible in the three-channel video, Tea Time, shown at Galeri Nev İstanbul in 2017. Showing us the production of glassware in a factory, Tea Time draws the viewers into an optical space reminiscent of hell with the close-ups of liquid glass that look like the leaks out of the magma layer. The artist’s increased interest in recording the visible forms of energy makes it possible for him to add his aesthetics new dimensions by means of the opsigns that indicate the places beyond this earth - hence the subterranean, extra-terrestrial and imaginary spaces.

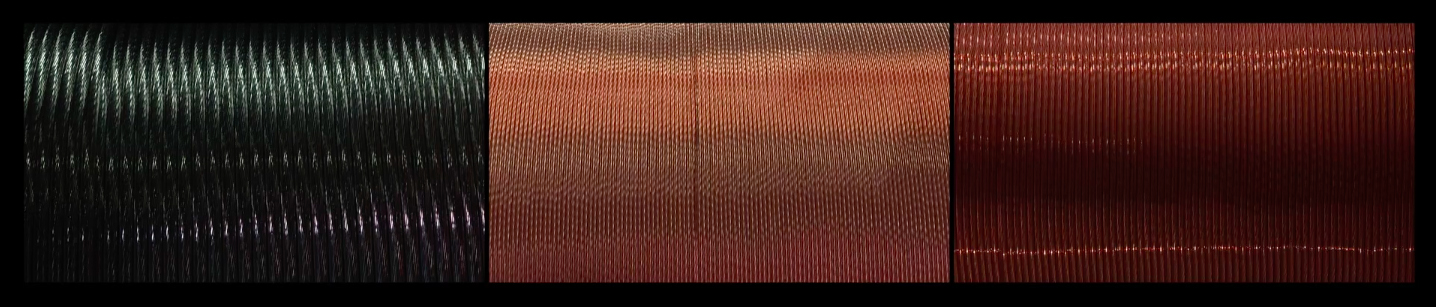

The tracing of light that reflect from various sources, and then off different surfaces seems to have turned into another prominent trajectory in the recent works of Kazma. It is possible to say that his video, Electric has been configured on that very trajectory, much like Subterranean. In this three-channel video work, which represents the most minimal editing amongst Kazma’s works, we watch steel, aluminum and copper wire netting produced for power lines reel on the mass production line. As the images follow up on one another, the only thing that takes place is this reel. The light that shifts in line with the reeling direction of the netting continues to reverberate and fluctuate on shiny surfaces throughout the video. We may consider Electric as a moving, abstract painting. The artist’s interest in juxtaposing the abstract forms he comes across with in the settings where he shoots his films is also apparent in Subterranean: the rusty surfaces converging on the two-channel video remind of the color studies of Rothko. Paul Ardenne notes that this predilection of “instilling pictorial qualities into video images” is a characteristic of the video-painting genre, which is represented by the likes of Bill Viola, Bill Coleman and Wilson Brothers. Ardenne also points out that the video-painting of Kazma does not amount to the rejection of videographical qualities as in François Parfait’s work, and states that they are equally painting and video. 16

Ali Kazma, Electric, 2017.

Three-channel video with sound.

Gilles Deleuze compares cinema and painting at the bifurcation points of philosophical arguments introduced in his book, Cinema 2. Tomlinson and Galeta seek the source of his fascination with both cinema and painting in his analysis of Francis Bacon. What renders these two mutual is that they both add new dimensions to the conceptual structures of percept and affect; yet the percept should not be mistaken for perception, and so is the case with the affect and feeling. 17 Reinterpreting the production aesthetics of Ali Kazma based on the potential transmissions between videography and cinematography sheds light on the artist’s relationship with percept and affect. The optical and sound situations pursued by Kazma with a regime of image, which is free from a notion of present, call on the viewers to perceive the world and its beyond in all its naked truth. As for the affect of Kazma’s videos, in a place away from this horrific present we live in, they strengthen our desire to re-connect with this world, despite all its violence and unbearableness.

1- Directed by Alain Resnais, the screenwriter of the movie was Alain Robbe-Grillet.

3- Deleuze, Gilles, Cinema 2, London: Continuum, 2005, p.xii

5- ibid, p. xi

6- ibid.

7- ibid, p.3.

8- ibid, p.9.

9- Deleuze, Gilles, Cinema 2, London: Continuum, 2005, p.26

10- ibid, p.32-33.

11- ibid, p.17.

12- ibid, p.4

13- ibid, p.12

14- “Learning How to Live”, interview with Fırat Arapoğlu, Flash Art, October 2013

15- Deleuze, Gilles, Cinema 2, London: Continuum, 2005, p.166

16- Ardenne, Paul, “Ali Kazma, İşler, 2005-2010”, İstanbul: Galeri Nev & Galerie Analix Forever, 2011, p.18

17- Deleuze, Gilles, Cinema 2, London: Continuum, 2005, p.xv

ABOUT THE WRITER

İbrahim Cansızoğlu

İbrahim Cansızoğlu, Istanbul based art writer and researcher.

He earned his undergraduate degree at Koç University Economics Department which he attended with full scholarship. He completed Sabancı University Visual Arts and Visual Communication Design Graduate Program with his MA thesis on aesthetics of moving image. At conferences organized by the University of Reading, the University of Hertfordshire and the University of Winchester, he presented his researches based on his thesis. He had a certificate from London Film Academy. He taught in film, visual theory, visual culture and contemporary art at Izmir University of Economics and Kadir Has University.

He worked at Galeri Nev Istanbul between 2012 -2015. He took on the task of curatorship in independent projects and in the context of Protocinema Emerging Curator Series in 2017. He continues to contribute art magazines Sanat Dünyamız and Art Unlimited with interviews and articles. He writes for the online art platform Argonotlar.