Blog

The Poetics of Flow: Reflections on Arrhythmia

15 August 2024 Thu

Ecem Arslanay presents an in-depth analysis in her article, examining the poetic roots of language and the blurring boundaries of digital forms through the works featured in the "Arrhythmia" exhibition.

Emerson proposed to regard language as fossil poetry, for just as limestone is composed of infinite masses of the shells of animalcules, language, too, has been made up of images and tropes. Perhaps this very movement caused it to forget its poetic origins. 1

The title of the exhibition is Arrhythmia. Therefore, I shall explore the word rhythm— as it is pronounced, written and defined in dictionaries — to uncover the poetic essence inherent in its etymological roots. The word rhythm originates from the Ancient Greek word ῥυθμός (rhythmos), derived from the verb ῥέω (rheo), which means "to flow." In this regard, the forgotten poetic origin of rhythm is "to flow" (rheo), while the "shells" that have formed around it are rhythmos, signifying "measure," "order," or "pattern." How has rhythm, once fluid, continuous, and uninterrupted, transformed into something rigid, tight, confined, fixed, regulatory, and divisive? This transformation compels an exploration of how rhythm has departed from its inherently flowing and ceaseless essence.

If we’d expended as much energy trying to find out how to communicate with trees as we have devoted to the extraction and transformation of petroleum, perhaps we’d be capable of lighting up a city by photosynthesis, or feeling vegetal sap run in our veins, but our Western civilization has specialized in capital and domination, in carbon energy and extractivism, in taxonomy and identification, not in cooperation or transformation.

- Paul B. Preciado 2

Before delving into the etymological origins of the term rhythm within the framework of the exhibition, I wish to first scrutinize its external layers. This word initially conjures in me a profound sense of planetary arrhythmia. For centuries, discernible rhythms—such as the cycles of the sun and moon, the ebb and flow of ocean tides, avian migrations, and the blossoming of flora—have governed human perceptions of time. Yet today, human time is governed by subatomic rhythms tailored to the demands of capitalist economies. The entire globe is now calibrated by the movements of imperceptibly small subatomic particles. For instance, the duration for a photon to traverse a hydrogen molecule is measured in zeptoseconds—a trillionth of a billionth of a second. These exacting measurements fine-tune production while fragmenting daily life into infinitesimal "ticks" with precisely defined durations, steps, resources, and actions. These commodified ticks hasten and disrupt the planet’s grand, profound, and ancient rhythms, leading to shifting seasons, altered migration routes, and collapsing ecosystems. 3

Mat Collishaw, “Even to the End III”, 2023.

Matt Collishaw’s video Heterosis portrays the intricate process of a grand clock mending itself after a breakdown. This mechanism involves disassembling the relentless small clock to facilitate its own reconstruction. In this desolate future, humanity has become extinct, having absorbed all the toxins they 4 once emitted through a body metaphorically vast enough to encircle the globe twice and a half. Ultimately, human metabolism is but a minute fraction of a grander ecological cycle. The world no longer witnesses the creation of new continents from plastics, the establishment of nuclear test islands, the mining of ocean floors for minerals, the poisoning of rivers, the conversion of forests into farmlands, the saturation of soil with chemical fertilizers, or the pollution of the atmosphere with greenhouse gases. Only plants and paintings endured. Collishaw’s vision of a post-human future at the National Gallery echoes the protests of climate activists who invade museums and stage dramatic demonstrations before artworks, questioning, "What holds more value: art or life? Is your concern more with preserving a painting or with safeguarding our planet and its inhabitants?"

The fact that the setting is a museum and Collishaw's intention to compare the historical price differences between oil paintings and hybrid flowers leads me to the issue of taxonomy. This theme is distinctly felt in his other works in the exhibition as well. For Heterosis, Collishaw states, “The artwork is a Vanitas portrait in a way, a depiction of the man's hubris, our desire to create exquisite cultural emblems in the form of magnificent oil paintings, and the neglect of the natural forces that govern the planet.” 5 His statement recalls the scientific taxonomies from Aristotle to the present, which position humans at the top and rank everything else according to human interests within a hierarchy of being. Are human-made art objects more valuable than stones, soils, oceans, birds, and flowers? Why impose sets of "measure," "order," or "pattern" (rhythmos) on being, when it could simply flow (rheo)?

Everything is an algorithm!

— Gregory Chaitin 6

One of the things humanity has learned to order is genes. For Collishaw, genetics is not merely a subject but an artistic method. His Petrichor exhibition, which ran from fall 2023 to spring 2024 at Kew Gardens, presented a dynamic NFT collection combining genetic algorithms with blockchain technology. Heterosis in Arrhythmia is part of this work. The National Gallery, modeled as if overrun by plants, hosts this NFT collection. The digital space offers an immersive environment where participants can cultivate and display their own flowers. In this digital hybridization experience, they discover that each token represents a seed containing a genetic code.

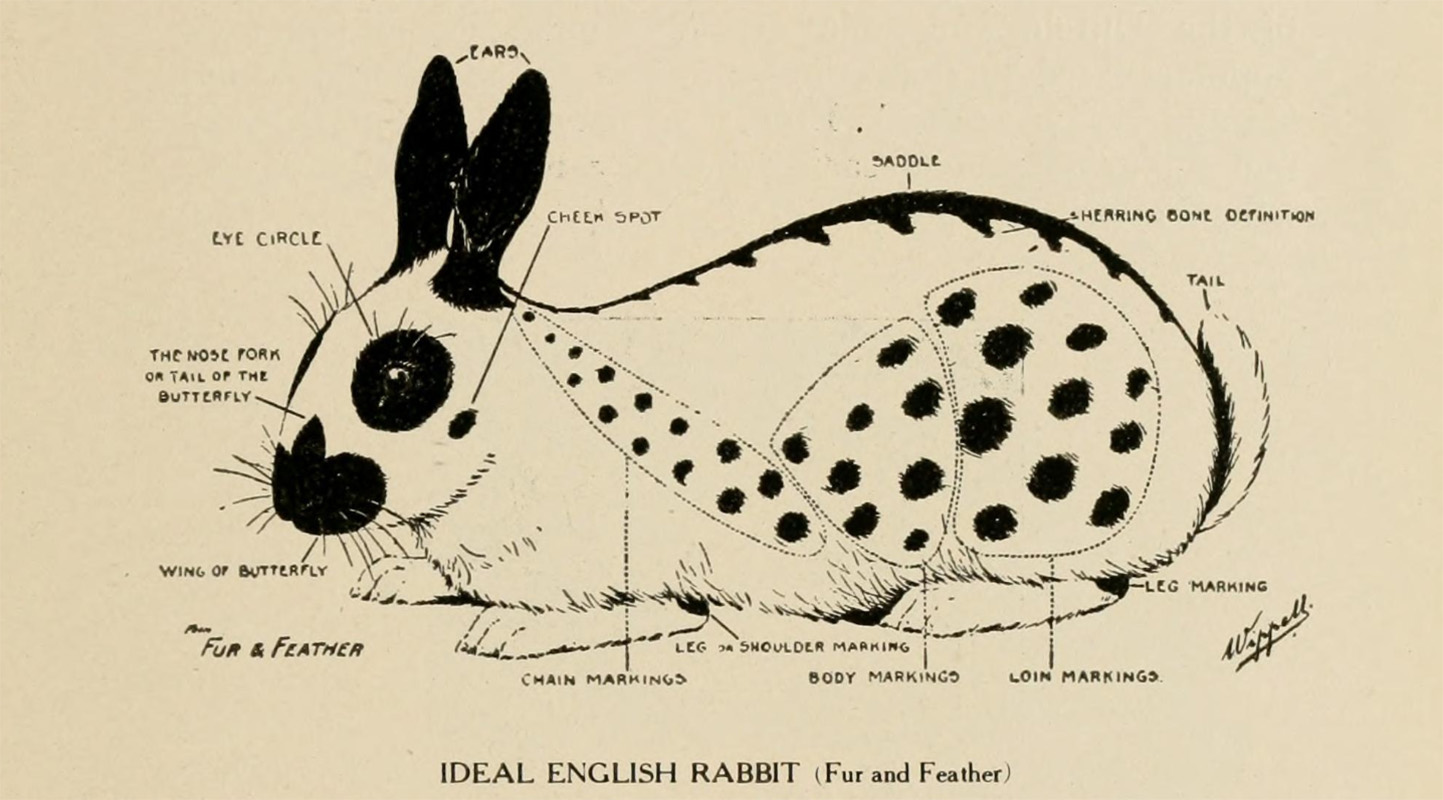

The American Pet Stock Standard of Perfection and Official Guide to the American Fur Fanciers' Association, Ideal English Rabbit diagram, 1915.

Crossbreeding can produce hybrids with traits from both parent flowers or hybrids inheriting recessive genes that are otherwise invisible. These flowers, varying in features such as petal count, length, curvature, edge texture, hardness, color, or degree of bloom, are given unique names by an artificial intelligence system drawing from the timeless and placeless The Library of Babel in Jorge Luis Borges's short story.

Can the production of knowledge about a certain existence — and its organization, classification, and patterning — alter the nature of that existence or recreate it? Can the boundaries between the biological and the digital blur? When the knowledge of biogenetics merges with computational knowledge, can the Tower of Babel be rebuilt? Can digital space offer an alternative substitute for a planet driven to ecological ruin through resource depletion? Considering that in 17th-century Holland, a rare tulip bulb was deemed more valuable than the oil painting depicting it, can a flower, which requires meticulous effort to cultivate and provides great aesthetic pleasure when grown, be considered an artwork itself? Can digital hybrids create a market frenzy akin to tulipomania’s tulip bulbs? Are the parameters determining their value rooted in beauty? What are the parameters that define beauty?

Being, which might otherwise flow is subjected to sets of "measure," "order," or "pattern" that serve various ideals. The ideal that Arrhythmia perhaps focuses on the most is the aesthetic one. Aestheticization is a form of artificial selection, an external decision imposed on the dynamics of natural selection within an ecosystem. Yet I am reluctant to use the term "external" because it implies a separation between humanity and nature, whereas I prefer to conceive of them as inherently entangled. As a microcosm, humanity (with its small clock) has, for ages, endeavored to comprehend its relationship to the macrocosm that encompasses it (with its grand clock). It measures its body against both smaller and larger entities within the universe. This pursuit of proportionality and perfection is evident not only in the Vitruvian Man but also in much earlier systems, such as those of Ancient Egypt or the ancient Hindu guidelines of Vastu Shastra. This quest for perfection involves reducing all bodies that constitute the universe's complex beauty, including the human form, to specific rules and templates. The term cosmetic is derived from the Ancient Greek word kosmos, which also signifies "order." Kosmos denotes both "universe" and "order." It is believed that this lesser-known meaning gained prominence through Pythagoras, who posited that the universe is an orderly place. 7

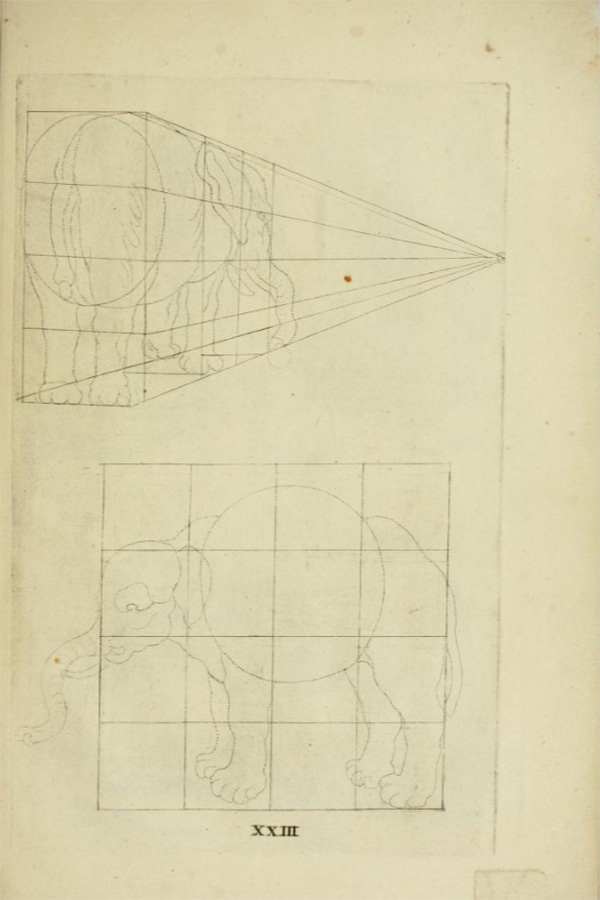

II. Crispijn van de Passe, The Perfect Elephant, 1643.

In the 17th century, as the systematic study of nature commenced, the artist Crispijn van de Passe II explored the concept of a perfect elephant. Fast forward to the 19th century, and we find another exemplar of the aesthetic ideal in the Ideal English Rabbit. This era was characterized by a pronounced quest for beauty, marked by the development of binomial nomenclature for classifying plants and animals. It was also a time when nationalism and national identity gained importance with the formation of various nation-states. Ernest George Wippell created an illustration that established the standards for the perfect markings of a specific rabbit breed. These examples, though seemingly absurd, illustrate the obsession with aestheticization.

Now, turning to Arrhythmia, two significant figures Collishaw drew upon for his work Pandora are Albrecht Dürer and Ernst Haeckel. Dürer, known for his Four Books on Human Proportion (Vier Bücher von menschlichen Proportion), represents the Renaissance—a period that encouraged acquiring knowledge through observation and experimentation, emphasizing perspective and anatomical accuracy. During this time, nature was considered not just an aesthetic object but a reality to be studied. Haeckel, on the other hand, reflects 19th-century Germany, an era marked by the Industrial Revolution and rapid scientific discoveries, as well as the rise of Social Darwinism and racist ideologies.

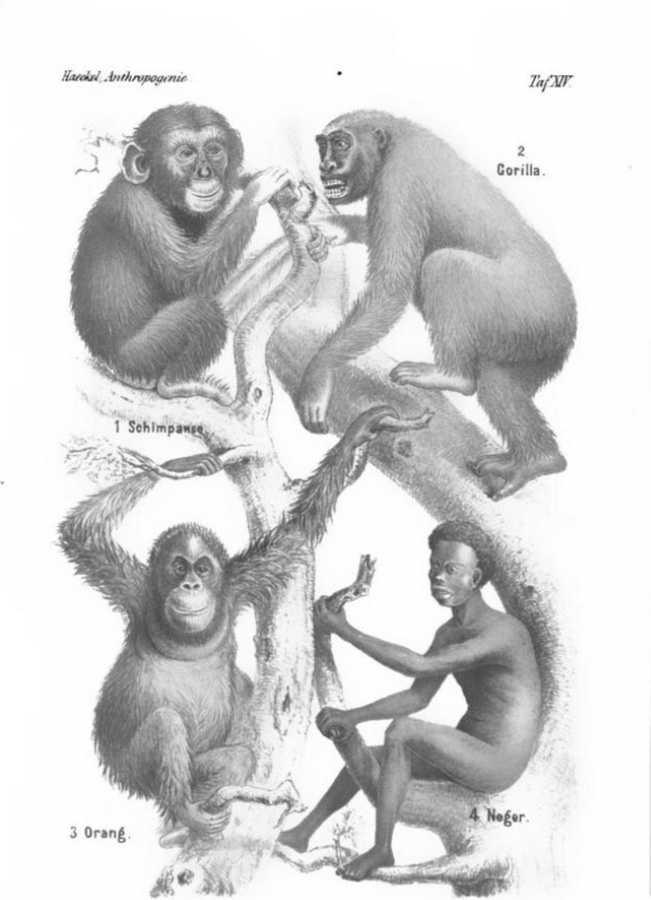

Ernst Haeckel, excerpt from the book Art Forms in Nature, 1904.

The pencil drawing titled Pandora masterfully intertwines Haeckel's illustrations of microscopic marine organisms with Dürer's woodcut The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, employing the capabilities of artificial intelligence. Dürer, celebrated as one of the pioneering artists to portray flora and fauna with scientific exactitude, converges with the works of Haeckel. Beyond his artistic endeavors, Haeckel was a distinguished naturalist, zoologist, and evolutionist, credited with coining numerous biological terms and discovering thousands of species.

In an era where species extinction is accelerating, Haeckel, renowned for his meticulous depictions of nature, his comprehensive tree of life, and his introduction of many biological concepts including ecology, also harbors a darker, less acknowledged side. Haeckel was a fervent eugenicist, advocating that human societies should be constructed on biological foundations. Influenced by Social Darwinism, he used these ideas to justify social inequalities and racial hierarchies. He depicted African races as more "primitive" and closer to ape ancestors, and supported the notion of "improving" the human race by eliminating disabled and sick individuals while promoting the reproduction of "healthy" individuals, predominantly Northern White Europeans. Thus, Pandora offers a compelling biopolitical commentary by hybridizing two distinct eras, styles, and technologies.

Let's continue our exploration of fossil poetry. The term "autopsy" originates from the Ancient Greek αὐτοψία (autopsia), which conveys meanings such as "seeing with one's own eyes," "seeing oneself," or "one's own view or landscape," being a combination of αὐτός (autos, self) and ὄψις (opsis; sight, view). This word underscores the intricate relationship between the observer and the observed, reminding us that the culture of meticulous examination and classification of nature often neglects its intrinsic vitality and will, reducing it to "dead nature" (still life). While the desire to see and interpret deepens our relationship with nature, viewing it as a passive object of knowledge or desire reveals a colonial attitude.

Notably, Romanticism, which opposed the rationalist and scientific approaches of the Enlightenment, was not free from exerting power over the landscapes it sought to immortalize. Consider the painters of the Hudson River School, who depicted America's vast beauty and its lands as awaiting exploration, with an underlying impulse for dominion. These European colonial artists frequently inserted themselves within the landscapes, suggesting an implied ownership over the territories they portrayed. I believe that this practice of embedding oneself within the landscape to signify possession finds echoes in the contemporary tradition of tourists posing in front of iconic vistas, a remnant of this colonialist culture.

— Psst, it said.

I turned to look. The fresh thistles and lavenders, not yet fully grown, gazed at me with the flavor of plums.

Hişt Hişt, Sait Faik Abasıyanık

In Whispering Weeds and Columbine, Collishaw directs his attention to humble roadside plants, typically overlooked as subjects of aesthetic appreciation. These videos, which breathe life into Albrecht Dürer’s Great Piece of Turf (1503), depict miniature landscapes that pulse with their own rhythms and wills. Rather than presenting pristine, vast, serene, fixed, and seemingly lifeless vistas, we encounter vibrant, participatory entities swaying within the intricate web of life. These plants, not grand or beautiful enough to be exploited, nevertheless persist. They communicate through volatile organic compounds, electrical signals, various chemicals, and mycorrhizal networks. Hosting pollinating insects, microbes, fungi, and animals, they are woven into the fabric of their ecosystem. Endowed with circadian genes, they experience the passage of time through their bodies in rings, perhaps inviting us to join their leisurely flow. If we were to silence our insatiable clocks, designed for productive efficiency and relentless consumption, and attune ourselves to the subtle rhythms, we might hear a gentle call: Psst!

Thomas Cole, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow, courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1836.

In Sait Faik Abasıyanık’s story Hişt Hişt, the enigmatic whisper of “Psst” (Hişt) seems to emanate from the unassuming roadside grasses, endlessly murmuring to themselves. This whisper extends beyond the grasses to encompass the grand landscapes that once enthralled colonizers: the babbling rivers, sparkling hills, rustling forests, buzzing insects, and chirping birds. Such a symphony of nature, in its multiplicity, is deeply resonant within Collishaw’s practice, which reveres this complex interplay of voices. His work critically engages with human ambition, insatiability, and destructive tendencies, yet does so with nuance rather than reductionism. In his recent video, Even to the End, he juxtaposes the historical role of Wardian cases — pivotal in the early 19th century for the global transportation of live plant species, thereby reshaping the Earth's ecology — with scenes of environmental devastation. This stark contrast is underscored by the haunting strains of Adagio for Strings, a composition inspired by Virgil’s Georgics, which reflects themes of agriculture, reproduction, and growth. The familiar melody, rendered almost trite by overexposure, evokes a poignant sense of melancholy, paired with imagery of ecological ruin that has become all too common. Given his earlier works that interrogate the manipulative rhetoric of mass media through the lens of visual excess, Collishaw’s choice in this piece is particularly significant.

This is precisely the simplest understanding of Aristotle’s famous theory of forms: the transition from one eternal form to another. These forms are, of course, ideal. Among them, existence assumes various poses, much like a dance.

Ulus Baker, Art and Desire

Collishaw’s exploration extends beyond the language of communication tools to encompass their underlying technologies. By melding innovations from the realm of media archaeology with contemporary advancements, he crafts complex, turbulent, and multifaceted natures. Technological artifacts, too, become woven into the fabric of life. A particularly striking example is the animatronic deer, Insilico, which utilizes a bespoke software developed by discourse analysts. This deer manifests a range of dynamic behaviors—sliding, stumbling, and collapsing—reflective of the intensity of online abuse targeted at Twitter profiles.

As Insilico embodies a struggle captured from the live Twitter feed through its robotic form, the exhibition's Sounding Sirens examines territorial conflicts between two animal species through the medium of a zoetrope. This zoetrope, which visually interprets the escalating jellyfish populations along coastal waters, employs a rotating platform and sequential sculptures to create an optical illusion of motion. Derived from the Greek words ζωή (zoe), meaning "life," and τρόπος (tropos), meaning "turning," the zoetrope metaphorically embodies existence by generating a dynamic array of poses and patterns from a continuous flow. Returning to the moment when I initiated the fossil poetry game: The word rhythm originates from the Ancient Greek word ῥυθμός (rhythmos), derived from the verb ῥέω (rheo), which means "to flow." In this regard, the forgotten poetic origin of rhythm is "to flow” while the "shells" that have formed around it are rhythmos, signifying "measure," "order," or "pattern." How has rhythm, once fluid, continuous, and uninterrupted, transformed into something rigid, tight, confined, fixed, regulatory, and divisive?

1- Language is fossil poetry. As the limestone of the continent consists of infinite masses of the shells of animalcules, so language is made up of images, or tropes, which now, in their secondary use, have long ceased to remind us of their poetic origin.

2- From a talk at Glad Day Bookshop, Toronto, January 22, 2020, launching An Apartment on Uranus.

3- I am quoting myself from another piece I wrote about time and a short film derived from that text. The essay: https://manifold.press/buyuk-saat-kucuk-saat-ileri-saat-geri-saat-yukari-saat-asagi-saat The film: https://vimeo.com/507972913 Instagram: @theclocksmovie

4- To maintain the poetic nature of the sentence, I used the term “human,” but I wish to emphasize the responsibility of economic and political powers rather than all of humanity in the context of ecological degradation. These are the true culprits of the environmental crisis. For me, this era should be referred to as the Capitalocene Age, rather than the Anthropocene.

6- Gregory Chaitin, “Leibniz, Information, Math and Physics” [online text], (2003), 9.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Ecem Arslanay

Ecem Arslanay is an Istanbul-based editor, writer, lecturer, architect, and filmmaker. She taught at Istanbul Bilgi University Faculty of Architecture (2017-2019) and currently teaches at Bahçeşehir University Faculty of Architecture (2021-present). As a Ph.D. candidate in architecture, her research focuses on the spatial qualities of the digital museum experience. Arslanay served as the production designer for the feature-length film “The Connected” (2022), supported by the Sharjah Art Foundation and Salt. She also wrote, co-directed, and co-produced the short film “The Clocks” (2021), which was a finalist in several international festivals, won several awards, and participated in various exhibitions and biennials. She is currently at a writer’s residency at Can Serrat, where she received a production grant to write the script for her next essay film.