Blog

Fluorescent Escape Lines and a Few Questions

16 May 2024 Thu

Rana Kelleci wrote an article on Niko Louma's “Symmetrium 2” in the exhibition “Hyper Digital Forces”.

It's a somber Saturday. The rain pours endlessly. I wander around the empty office desks. In the Perili Köşk, I gaze at the artworks hung on the walls that face away Bosphorus. Meanwhile, I pause to watch the view of the Bosphorus, which is as alluring as a painting. All shades of gray are being scrambled between the sea and the sky.

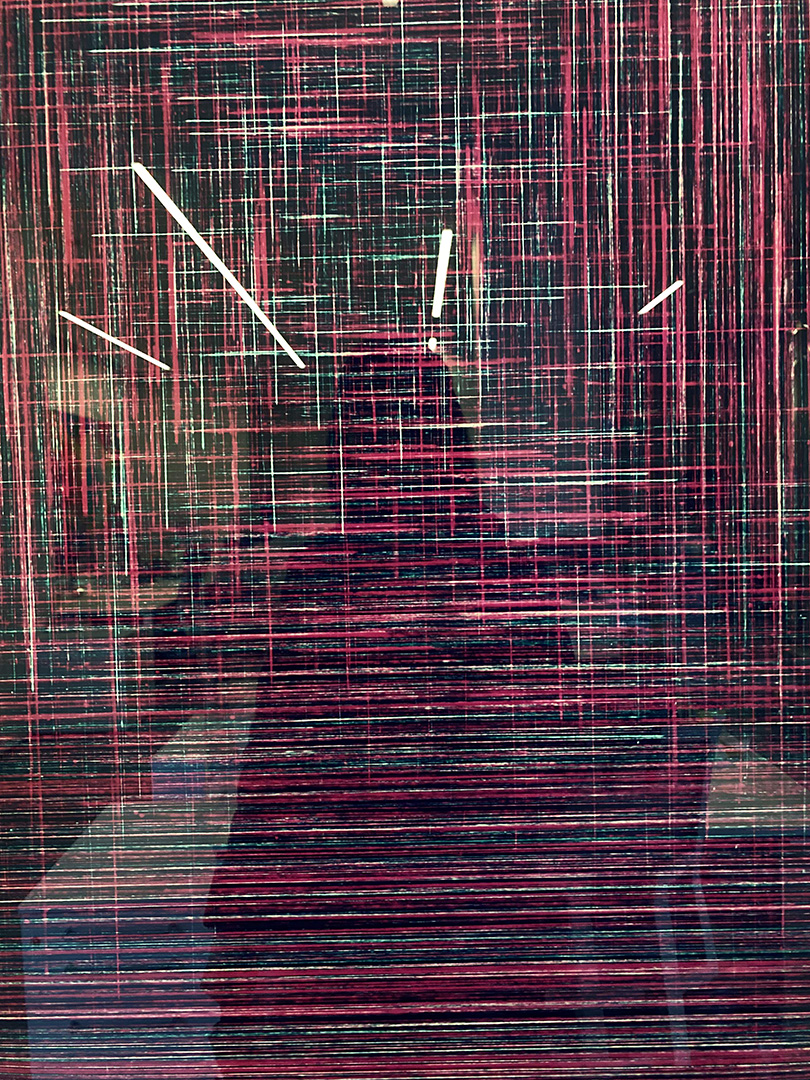

Though the offices are spacious and luster, the lights are turned on due to the overcast weather. In front of me, Niko Luoma's Symmetrium 2 stands between two windows opening to the Bosphorus. The first thing that catches my attention is the ceiling lighting in the form of lines reflected on the glossy surface of the work. The work is composed of a combination of vertical and horizontal, string-like lines that the artist created through various photographic manipulations during shooting. This seemingly haphazard combination creates a depth that draws the viewer inside. The office lights, which imply an onward movement as if traveling through a dark tunnel, are reflected as white lines on the surface, reinforcing the sense of depth; inevitably they have a say in the field of perception unfolded by the work.

When I look at the work carefully, I think that the lines were drawn by hand first and then erased, because the presence of a hand is sensible in the unsharpened lines. Yet, the artist has created this image by playing with the basic photography methods. Luoma has created built-up lines using the multiple exposure technique and through allowing light, the main requisite of photography, to fall on the photographic surface (the film) for different durations. In his text about the Symmetrium series, which includes the aforementioned work, he says that he uses light like a painter layers colors. 1 The treatment of light as materials like paints and brushes brings to my mind the camera obscura device, which revealed previously unknown properties of light and paved the way for discovering the means to create images with light.

Niko Louma, “Symmetrium 2”, 2009.

Photo: Hadiye Cangökçe.

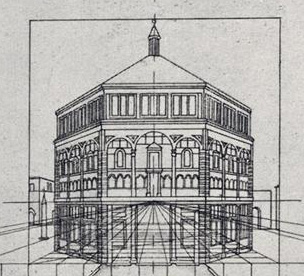

Diagram demonstrating Filippo Brunelleschi's perspective technique from a lost painting of the Battistero di San Giovanni, Source: Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, Max-Planck-Institut.

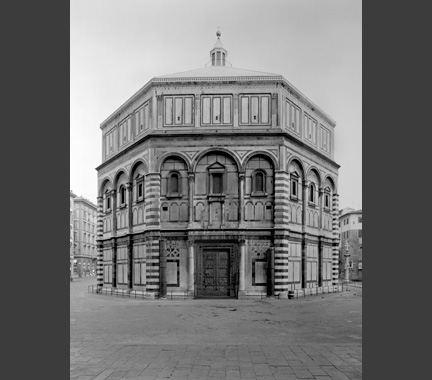

The Baptistery of St. John, Ralph Lieberman, Source.

Invented by the Arab mathematician and optical scientist Ibn al-Haytham, this device is the progenitor of the linear perspective technique and the camera obscura, a dark box (or even a room) with a single pinhole drilled into it. Light passes through the pinhole into this completely darkened box, reflecting the images of the world as they are (only upside down) on the opposite surface. Based on this device, the Italian architect Brunelleschi developed the technique of linear perspective in painting, the architect and theorist Alberti theorized how to construct a painting with perspective, and the artists of the Italian Renaissance began to take advantage of these inventions to transfer the visible world to the painting surface in the most realistic way. Paintings based on linear perspective gradually evolved into a way of seeing in which the world is shaped according to the viewer's point of view. 2 Recently, seminal arguments have been put forward about how this way of seeing connects with the Eurocentric narratives and the creation of a colonialist order. However, for the sake of the scope of this article, let us leave this information only as an insight into why ways of seeing are worth a conceptual analysis.

Niko Louma, “Symmetrium 2”, 2009.

Photo: Rana Kelleci.

My body as a viewer is reflected on the surface of Niko Luoma's work like the lighting fixture in the office. I am at the center of the work in case of a silhouette. The lines of light extending from the ceiling towards me resemble the lines of perspective or escape lines that a painter draws on his canvas when constructing a realistic composition. The escape lines start wherever the viewer is expected to focus on the canvas and extend to the ends of the canvas in the shape of a pyramid. At the most basic level, this technique, which imitates the eye's ability to see distant objects as smaller and nearer objects as larger, aims at the illusion of reality. Because to create a three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional picture surface, which is not spatial, it is necessary to mislead the eye and manipulate the sense of sight indeed.

When we follow the path opened by the camera obscura, the next stop after linear perspective is the camera. Since its invention, photography has always held a controversial position with the claim that it objectively captures reality. It should be noted here that whether photography intends to create the illusion of reality opens up a completely different debate on the political and ideological instrumentalization of the medium. After all, every realistic image, whether a photograph or a perspective painting, questions whether it is real or an image. As we look at a realistic image, reality turns into an open discussion.

Is what is seen real?

What is visible and what is not visible?

According to whom is what is seen as real?

Why is it real or not?

Is there room for a reality other than what is seen?

Niko Louma, “Symmetrium 2”, 2009.

Photo: Rana Kelleci.

On the glossy surface of Symmetrium 2, when the viewer encounters himself, the connection between the position of the viewer and reality begins to become visible, and a space opens up for questions. In other words, in the space opened by the work, one can become aware of one's own gaze, and try to understand it. New mental paths that lead to the idea that there may be different ways of looking at reality start to appear.

How do I see?

From what position am I used to looking?

What influences my gaze outside of myself?

How are my eyes conditioned?

How do I tend to see what I look at?

The lighting fixtures on the office's ceiling are reflected on the photograph's surface and underline our being here and now in front of the work.

What kind of reality am I in here and now?

Who am I standing here today, looking at this work? ...

Luoma says the following about the Symmetrium series: “I had in mind to create what a photograph cannot be. Free of the past, abstract, and a first-time image, only connected to the present that it represents… I wanted the photograph to have its own present, always open. Symmetrium works are about being.” 3 It can be said that the present of Luoma's photograph embraces both the present of the viewer and the present of the space. My present while watching this exhibition and this work, the present of the Perili Köşk, the present of other visitors, the present of the security guards watching their areas on the floors...

The fluorescent escape lines added to Luoma's composition from the present of the office space strengthen the depth of his composition while at the same time reminding us to remember where we are as viewers. In other words, it reminds us of our presence in the space, we are called back to the consciousness of the empty desks around us, the gray carpeting under our feet, and our presence on this dim Saturday afternoon by the Bosphorus. The museum staff moves slowly through the exhibition space, cars pass by the coastal road, and the light continues to take on all shades of gray around the edges of the rolling waves.

2- Belting, Hans. 2012. Floransa ve Bağdat Doğu ’da ve Batı’da Bakışın Tarihi. Çev. Zehra Aksu Yılmazer. İstanbul: Koç Üniversitesi Yayınları.

3- Yazarın çevirisi. https://nikoluoma.net/symmetrium/